Wattpad just posted their interview with me for my Watty Award-Winning short-story, “The Omens of a Crow.” Check it out if you’re interested!

Wattys 2018 Winners Spotlight: Dakota Kemp

Wattpad just posted their interview with me for my Watty Award-Winning short-story, “The Omens of a Crow.” Check it out if you’re interested!

Wattys 2018 Winners Spotlight: Dakota Kemp

I know it’s been a long time since my last post, but there’s a good reason for that. I was at the National Training Center in the Mojave Desert for a month-long field exercise. That counts as a good excuse, right?

Anyway, I returned from exile to some exciting news: My latest short-story, The Omens of a Crow, won the 2018 Watty Award The Heroes!

For those of you who aren’t familiar, the Wattys is an annual contest hosted by the reading/writing website Wattpad, who selects the best stories on the site from the pool of tales posted for the entire year. This year, 60 stories were selected to receive Watty Awards from a pool of approximately 164,000. Omens was one of them! As I mentioned before, it received an award titled The Heroes.

Here’s how Wattpad describes the award:

The Heroes

This award celebrates the stories that introduced us to characters we related to, who made us feel for them, who showed us a new way of looking at the world.

A great character stays with the reader long after the story’s done – these stories did just that. They stand out in our mind, these characters you’ve invented. They’re flesh and blood and prose. Perhaps they’re demi-gods like Percy and anti-heroes like Achilles. They have the spirit of Katniss Everdeen, Bilbo Baggins, and the Pevensies as they take on adventure, and they instill fearlessness in us like Harry, Hermione, and Ron as they charge into the unknown. Their words mean something to us. They are our enemies, our friends, and our fantasies. They are our Heroes. They are flawed and complicated, but we can’t help but love them. We celebrate your imagination and the amazing characters that you have given us!

I consider it quite an honor to have a story of mine compared to such titans as Percy Jackson, The Iliad, The Hunger Games, The Hobbit, The Chronicles of Narnia, and Harry Potter. Makes a man like me a little woozy. (Don’t catch me if I faint. Just let me sleep. I think I’ve earned the rest).

That’s the news. Color me surprised and flattered. If you’ve yet to read The Omens of a Crow, check it out on Amazon, Smashwords, or Wattpad! And, as ever, be sure to leave a review! (Disclaimer: Omens contains mature content and is intended for an adult audience.)

News for all my fellow science fiction and fantasy fans: it has come to my attention that one of the great sci fi and fantasy writers – indeed one of the founders of modern fantasy – passed away in January. Ursula K. Le Guin’s death was as markedly quiet as her work, though her writings somehow managed to combine that quiet success with insight, lyricism, and a world’s worth of endlessly compelling themes.

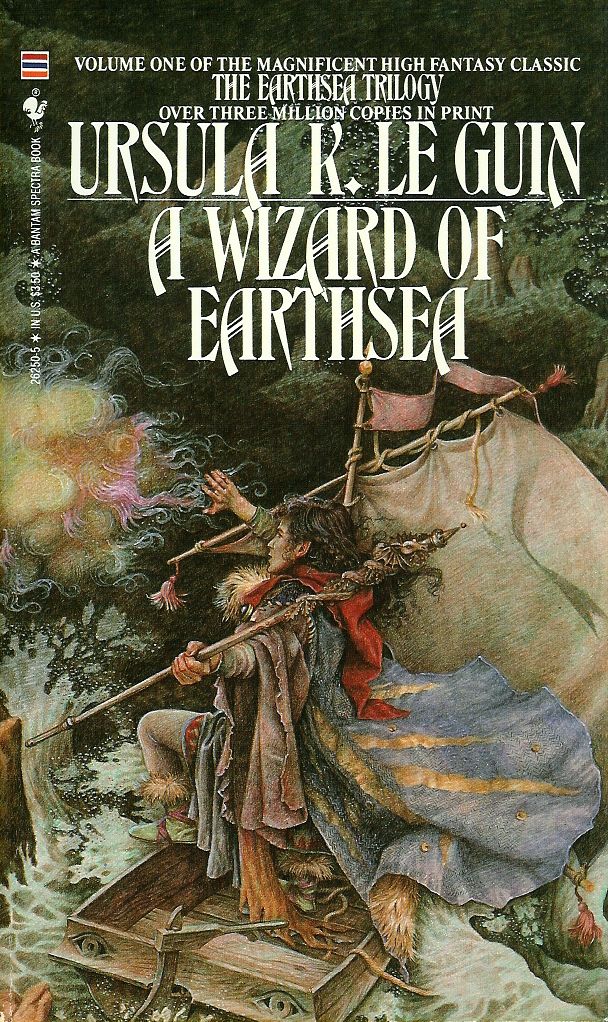

Unfortunately, I’ve not read many of Le Guin’s contributions, but the few I have experienced had special influences on my journey both as a reader and a writer. In particular, A Wizard of Earthsea, that classic of fantasy literature on par both in style and prose with The Chronicles of Narnia and The Lord of the Rings, touched me deeply. It was perhaps the first book where I realized what profound meaning, symbolism, and import could be infused into the pages of a written work. I don’t think I’ve ever fully recovered from the powerful conclusion of that tiny volume, which managed to hit me as hard as any thick tome. What a powerful tale she wove with Ged, one that mirrored in many ways my own, as I’m sure it has for many a reader over the years. That struggle of growing up, at once both unsure and utterly confident, climbing to the top of the world only to fall upon reaching the zenith. Pride has knocked the wind out of me on many occasions, just as it does Ged. But confronting our faults and continuing on is one of the true themes of Earthsea, and I found myself bettered by the experience. Truly great stories remind us of powerful lessons we already know, and the reminder is often beautifully given. A Wizard of Earthsea gave me a great many such touching reminders, and for that I will always be grateful to Mrs. Le Guin. If you’ve never read Ged’s tale, I encourage you to pick it up. It is a lyrical, poignant journey delivered in sparse but haunting words (and it’s the original book to introduce the “Hogwarts concept” of a wizard school made famous by J.K. Rowling in Harry Potter). Other groundbreaking works by Le Guin include The Left Hand of Darkness, The Dispossessed, The Lathe of Heaven, and The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas.

Thanks for all the wonderful stories you brought to the world, Mrs. Le Guin. Your ability to touch us both emotionally and intellectually will be missed.

Have any of you been moved by Ursula K. Le Guin’s stories? Which are your favorites? Are there any that affected you as Ged’s did me?

The big news in storytelling right now is Disney’s new live-action version of Beauty and the Beast, which is causing quite a stir with not only its enormous box office haul, but also its social commentary. I’m writing, of course, about the uproar over Disney having included their first-ever gay character. (Symbolically they’ve already done so in a previous prominent Disney film, but, from what I understand, Lefou is the first to be openly portrayed as gay). Now, we’ve already discussed my views on agenda in stories, and I’ve not yet seen B&tB, so I’ll refrain from commentary on if they violated my number one rule. I will have to present some opinion here, however, and the blowback could get nasty. I struggled for a long time trying to decide if I should write a post over this, since it’s such a charged issue. I certainly have no desire to introduce politics into my website’s storytelling vibe, but it is the biggest storytelling news of the day, and storytelling, in all it facets, is what I claim to cover.

So, without further ado: Beauty and the Beast, a gay Disney character, and immediate bickering. This is the big storytelling news right now, and for the life of me, I can’t figure out why. I’m left wondering if this should actually be a big deal, because it all boils down to one fact.

This is America, ladies and gents, and – call me crazy – but in America, you’re free to live however you want, provided your actions don’t endanger others.

If you want to live a homosexual lifestyle, be my guest. You are an adult and an American. You’re free to live how you see fit. If you believe that homosexuality is morally wrong, then, by all means, continue to believe that. You are an adult and an American. You’re free to believe as you see fit. When you start trampling on each other’s right to freedom, that’s when I get cranky.

No, you can’t live in a bubble where you are never exposed to same-sex couples. Newsflash, you live on a planet with other people. You will run into individuals/lifestyles/moralities/actions/cultures/viewpoints with which you do not personally agree. Other people are not required to behave as you believe they should, nor are they required to share your principles. If that were the case, society would have already agreed to my proposal for weekly worldwide watch-parties of The Lord of the Rings.

No, homosexuals, you cannot live in a utopia were everyone agrees with your lifestyle. Newsflash, you live on a planet with other people. You will run into moral codes that do not jive with your personal views on morality. Other people are not required to accept you, your lifestyle, or anything at all, really. This is America, remember? In America, people are free to live as they want, believe as they wish, and support what they like.

Wow. That got to be quite the rant. If you’re ready for a conclusion, here’s my take on the matter: People are free to include gay characters in their stories. Why? ‘Cause ‘Murica. People are free not to like that a story has gay characters and refuse to support it with their business. Why? ‘Cause ‘Murica. We may not be the most virtuous or enlightened country on the planet, but by God we’re the freest. And the thing about freedom? There’s a good chance it won’t ever foster the best in us, but it does allow us the chance to be best we can be. In my opinion, that’s really all we need.

I know I’ve not had new content for a while, but I’ve been preparing an extra-special post for you. In fact, it’s become so special (and lengthy) that I’m going to break it up in to four or five separate posts.

This marks the first of my story analysis entries for my theme, The Power of Stories. If I get a good response, I’ll keep doing these. If not, I’ll probably stick solely to posts on storytelling in general. Hopefully, we can get a good discussion going, because I’d like to hear others’ thoughts on these stories as well. Let’s take an in-depth look at one we love.

As most people reading this are no doubt aware, I’m a huge fan of Roosterteeth’s hit web series RWBY. The fourth volume of this American anime concluded only a few weeks past, so I thought now would be a great time to break down the latest volume to see what worked, what didn’t, and why this story is so powerful.

Is it necessary for me to call spoilers? We’re going to be discussing the fourth volume of an ongoing series. Do I really need to point out that there will be major plot points, characters, etc. discussed that could ruin the twists and turns? Just to be safe, for the people who also need the giant CONTENTS ARE HOT label on the sides of their coffee cups: SPOILERS AHEAD. Do not continue if you’ve not watched RWBY Volumes 1-4.

I’m going to break down stories in list form, a kind of pros and cons list, with the most important issues first, ranking to the least important as we proceed.

So, without further ado, my story evaluation of:

RWBY Overview

RWBY is hard to categorize for a lot of reasons. It’s visual style most closely resembles anime (especially in this fourth volume), but beyond that and a few derivative style quirks, it has few of the hallmark Japanese-esque qualities that traditionally mark a show as “anime.” Its characters and world are based off of fairy tales, but it doesn’t fit in that category either. The Brothers Grimm type folktales are simply used as an inspirational backdrop. The humor and dialogue have a distinctive Roosterteeth flair, of which I’ve not seen the likes in anything other than a RT product. It has loads of action, but that action is in a style more akin to a video game than a film or anime. Even the world setting can’t decide if it’s science fiction, medieval fantasy, or cyberpunk! My point is that RWBY doesn’t fit anywhere. And that’s awesome! It defies not only genre boundaries, but also any form of format classification, and that’s part of what makes RWBY such a great experience. While it borrows from many sources, it is somehow utterly unique, in a cross-genre, cross-media niche of its very own.

If you’ve read to this point, I’m going to assume you’ve seen the show through Volume 4. If you haven’t, leave now. Go read something else cool on my site.

Now, if you’re still here I’m sure you’re up to date, but I still feel compelled to share some backstory on Volume 4 as a foundation for my evaluation. While counting down to the internet airing, I was equal parts worried and eager for RWBY’s next installment. My excitement was caused by the long interim since Vol. 3’s emotional conclusion, but I was apprehensive for two reasons. 1) This would be the first volume of RWBY with no input by its mastermind. Monty Oum, RWBY’s creator, had worked on several scenes for Vol. 3 before his untimely death, but the fourth volume would be devoid of his influence. (Excepting, of course, his vision for the long-term series arc, from which co-writers Miles Luna and Kerry Shawcross are working.) Needless to say, losing the heart and soul behind a project means that it will be affected, and I was worried to see how. 2) Roosterteeth Animation decided to make the switch from Poser, the animation platform chosen by Monty for work in the first three volumes, to Maya, the most widespread animation platform in the world. Now, I understand RT Animation’s decision to do so. They’ve been expanding rapidly with the success of RWBY, and new employees are already proficient in Maya, which cuts down on training time for an unfamiliar platform like Poser. Also, one of the constant criticisms for the first three volumes was the animation, which many viewers believed inadequate. Personally, I was happy with the Poser look, and the volumes were looking better and better with each season, but RT agreed with the need for an upgrade, which I suppose I can understand. For these reasons, I feared the show wouldn’t feel the same, and to a certain extent I was right. Let’s dive into RWBY Vol. 4!

“All worthy work is open to interpretations the author did not intend. Art isn’t your pet – it’s your kid. It grows up and talks back to you.” – Joss Whedon

The idea that I discussed last week – that a storyteller’s purpose is to give questions, not answers – rankles some people, most of whom are storytellers who regularly ignore this purpose, thinking themselves wiser than their audience. My post from last week does require some caveats, however. Once we accept the purpose of the storyteller, there is a second truth we must embrace: Your voice matters. It may not be your place to tell the audience what to think, but it is your job to tell a story, and one that is ultimately meaningful.

Your storytelling voice matters, and sometimes it matters in ways you never expected.

Now, I know the quote that I used this week is from a storyteller who regularly violates the purpose of storytelling. No one knows better than I the appalling number of times Joss Whedon has downright browbeaten his audience with opinion, but that doesn’t change the fact that, when he desists from forcing a specific agenda, he is a peerless storyteller. And the discernment shown in the above quote is striking.

The first part of my point is that your voice matters, and that’s important to grasp before we move on to the next half. Your artistic voice matters. I may repeat it a thousand times in this post, but it’s an important truth to embrace as a lifelong artist. If you don’t embrace it, you won’t be a storyteller, plain and simple. You’ll give up. You’ll stop telling stories. If you believe you’re shouting into the void, how long do you think you’ll sit around listening to your own echo? Not long for some. Years for others. But, if you don’t embrace the idea that your art has unique value, you will eventually quit. Embrace this truth. You’ve got a voice, you’ve got questions to give the world, and only you can deliver them the way you do.

If you accept that, we can move on to my second point, summarized by Whedon as “interpretations the author did not intend.” Often, your work will become something you never planned for it to be. One of the greatest facts about this world is that people are different. They interpret life and experience and art in a way distinctive to themselves. You don’t always get to choose how your art affects people, and that’s okay! After all, you may be the god of your stories, but that doesn’t make you the God of this one. Your only duty is to tell stories to the best of your ability, putting 110% of your work and effort into each one. And don’t apologize for them! Never apologize for your art, whether it is received poorly because it is interpreted as you intended or not. It’s your art, and just as you’ve no call to force your audience to think as you do, they’ve no call to silence your voice. Tell your stories – without preaching, without bowing to the whims of social critics – and tell them well. Tell them with care and with meaning and with purpose, but don’t fret over interpretation. Sometimes people need something specific from a story, and yours provides it. Life influences people to equate what they see in art with their experiences, and you can’t control that. So don’t try to!

Storytelling, like life, isn’t about having it all together or being in control. It’s about doing the best we can, and trusting that something larger than ourselves will handle the rest.

Tell your stories, because your voice matters! But relinquish control, because worthy art is always bigger than the person who made it.

“The purpose of a storyteller is not to tell you how to think, but to give you questions to think upon. Too often, we forget that.” – Wit, The Way of Kings by Brandon Sanderson

What is the role of the storyteller? He or she brings a tale to the audience, yes, but what is the purpose of doing so? It could be to entertain. After all, entertainment is the reason most of us regularly partake of stories in the first place. In fact, a story can be said to have failed in its purpose if it doesn’t entertain, whether through humor, excitement, suspense, pathos, or some other means. I agree that a storyteller must entertain, and cannot fulfill the real purpose of the profession if he fails to do so. But entertainment is not the significant role of the storyteller.

In a world that always has been, is now, and will ever be gray, we storytellers have, by and large, abominably bungled the presenting of that fact. The present is no more polarized than times before – humans will always find reasons to break into opposing camps, extolling their side’s virtues while vilifying their “opponents” – but we are not any less divided either. Which proves only that we’ve done a poor job of learning from the past. Right and wrong are rarely what separate people and their enemies. It’s different standpoints, different perspectives. Just two sides holding disparate views about what is most important. What does this have to do with storytelling? Why, it shows that much of the time we have forgotten our role as storytellers! Many of us are as guilty as anyone of dividing the world, cutting it up into stark sections of black and white, of using our stories to cram agenda down our audience’s throats.

The reality, however, is this: The role of the storyteller is not to tell people what to think, but to teach them how to think for themselves.

We storytellers often try to influence how people think and act, though it is not our place to do so. Rather, our goal should be only to get people to put that brain between their ears to work. Questions! The storyteller’s duty is to present them with questions upon which to ponder, because thinking for ourselves, not merely mimicking what we’re told to think, is the only we grow.

So we must make them think. We coax them into evaluating life – both the big and small things – on a deeper, more personal level.

You might say: “Come now, Dakota, all storytellers build their stories around theme. Without theme, without purpose, a story is just a jumble of words or images. Themes are all about trying to influence people to act a certain way.” You may be right. Themes are important. They do provide purpose to a story. But I will say this:

Good themes are about questions, not solutions.

I absolutely write themes into my stories. I write with a purpose in mind, but always with the intention of revealing universal principles, thoughts, and feelings, never blatant conclusions that READERS MUST ACCEPT. I want my readers to see what I present in my stories and use it to consider who they are. I want questions – glorious, inspiring, dark, bitter, infuriating questions – to be the product of my work.

We all want to change the world in some fashion, don’t we? Of course we do! But consider how you do so, otherwise you may end up changing it in ways you would never wish to have done so, because the forcing of change often backfires. Don’t force it. Promote it. And more than that, accept the fact that you are not, nor ever will be, fully in control of change. Change cannot be forced on people; you will harden them against it. Change can only grow from within, as they consider things for themselves. The movie Inception is a great visual representation of this. People will often reject the ideas forced on them. But the ones that seem organic? Those ideas shape the world. Remember: The ideas you plant without rancor, without design, without insisting people should think a certain way are the ones that will be deeply and seriously considered. Don’t browbeat them. Inform them.

“Here is an interesting concept, reader. Perhaps you should consider it, and decide how it affects the world.”

“Here’s an issue we struggle with in today’s world, viewer. It’s there now, front and center in your mind, why not analyze how you see it? What you think about it? How we might be able to fix it?”

As a storyteller, think of the philosophy you champion when you try to force an agenda on others. This, in a nutshell, is what you are saying: If only the whole world thought as I do we would never have any problems! You’re absolutely right. We wouldn’t have problems. Not of a certain sort, at any rate. What we would have is stagnancy. Apathy. A world full of boring people who might as well be vegetables for all the stimulation we would receive from others, since everyone would be carbon copies. We would all be mindless clones of one another, espousing the exact same things. I don’t want to live in a world like that. Do you? Then why bully others with your stories? You’re not changing the world for the better when you tell people what to think, but you most certainly are when you help them learn to do so for themselves.

Asking tough questions is to be encouraged in storytelling, pushing agendas is not.

The example this week is going to be The Jungle by Upton Sinclair. The story, if you’ve not read it, starts out great. There are some excellent scenes that really hit you with a new appreciation for tragedy, and the early stages raise some provocative questions about rampant capitalism. By the end, however, it has devolved into a soapbox, a pedestal for what can only be labeled as propaganda. And you know what? The novel did change things, though not in the way Sinclair intended. The Jungle did not convince the American people of the benefits of socialism (the agenda which Sinclair pushed with all the subtlety of a Super Bowl half-time show), but it did expose horrific conditions in the meatpacking industry. In effect, the agenda espoused by The Jungle fell flat, while the questions raised by Sinclair’s tale inspired a generation to enact change in what had been an oppressive, unsanitary industry. What would have been the result if Sinclair had simply provided his readership with thought-provoking questions about socialism instead of cramming it down their throats? We’ll never know. Because he didn’t.

“But The Jungle is a classic!” I can hear the outrage from the peanut gallery even as I write this. “How dare you use a literary work, hailed the world over, as an example of abusive storytelling?”

The answer is simple. To a certain extent, people like to be told what to think. Life is easier that way. We can either eagerly embrace or easily reject what is shouted at us, because we are given no reason to give such blatant messages serious thought. If we agree with a brazen message? We heartily agree and move on. If we find it out of line with our preconceived notions, we either put the story aside or ignore its obvious propaganda and continue on with the story. When we are told what to do, we don’t have to go through the hassle of carefully considering life. We simply agree or disagree out of hand. Passivity is easy. Scrutiny is hard. Ladies and gentlemen, storytellers are not obliged to make life easy for the audience. Quite the opposite, in fact. It is our purpose to make certain that they never stop moving forward, never cease growing and learning and being.

So let’s make a resolution, shall we? No more agendas. Only questions. People will learn to be who they need to be without our sanctimonious preaching. Our audience, after all, is no less human, and they’ve got more to teach us than we ever could them.

Did my post about questions raise any questions? Comments? Rants? Do you find it ironic that I used a post about not using stories to tell people how to think to tell people how to think? Let me know!

Go on! Go introduce the world to some questions!

“There’s power in stories.” – Varric Tethras

I’m a bit of an oddball. Always have been. But I’m not ashamed of that fact. It makes life more interesting for me. I like to imagine it makes me enigmatic as well, but that’s probably just me indulging my not inconsiderable ego.

The point, however, is this: I’ve got some unusual ways of looking at the world.

For instance, if you asked everyone on the planet about the meaning of life, what do you suppose the answers would be? They would be far-ranging, but I think we could expect a dozen or so common themes around which the majority of people’s answers would cluster. We’d hear about love and service to others, adventure, experience, survival, proving your worth and living simply. We would most certainly run into people who believe life was about serving God, just as we would discover that many people believe life has no purpose at all.

But me? I think everyone is wrong. And I think everyone is right. Because I believe the meaning of life is all of these things. It just depends on what story is being told.

The purpose of this website is the same as that of life. Story. In the end, everything comes back to story. Everything about human existence concerns and hinges on narrative. Each individual life is a story, every day is a story, every activity, every event. That’s what history is – stories that last. Even religion is made of stories, the ones that inspire or motivate us to be better. Stories are all around us, in everything we do. Life, after all, is just one vast saga. We’re all characters, and we each have a part to play. It’s all about stories with us, and, in the words of expert storyteller Varric Tethras, there’s power in stories.

That’s why storytellers do what we do.

The careers of all storytellers – authors, filmmakers, playwrights, video game developers, even songwriters – are built on the assumption that stories are powerful. That stories change people. They challenge us to grow and explore, to look at the world in new ways. They cause us to re-evaluate the world and our place in it. Research is beginning to suggest what storytellers have known for eons: that stories affect how we think, how we perceive life and the world around us, and, by extension, the way we act. But we don’t really need new research to tell us that, do we? The evidence is around us in daily life, and it is apparent in even the most cursory glance through the past. Stories have proven throughout human history to be far more than just art or entertainment. They are often radical agents of change. To demonstrate this, I could cite a number of stories from any one of the major religions in the world, but that seems a bit too obvious. How about The Illiad? Homer’s epic influenced generations of Greek tradition which ultimately, in turn, affected every aspect of western civilization. It also kept in place a Greek warrior ethos that radically reshaped the world through the actions of Alexander the Great. (Funnily enough, Alexander was not Greek, but the Macedonians of his time adored Greek culture and emulated it in almost every way.) Alexander was raised on The Illiad. He was greatly inspired by the ethos it espoused, and he believed himself to be a continuation of its epic. A new Achilles for a later age.

Where would the world be now if not for The Illiad’s influence on one of the great shapers of history? Somewhere very different, that is certain. This is just one example out of thousands, tens of thousands, of examples that could be used. Stories are powerful; the world in which we live has been shaped by story as much as man.

So, have I gotten my point across? Are stories powerful, or am I just a ranting lunatic? (The latter is very probable.) If you agree that stories have almost unlimited influence in our lives, then I invite you to subscribe for more posts. I’m going to try to get some discussion flowing in the future, that way you don’t have to read only one person’s highly biased opinion. After all, the internal and external conversations brought about by stories are what unleash their change-creating potential!